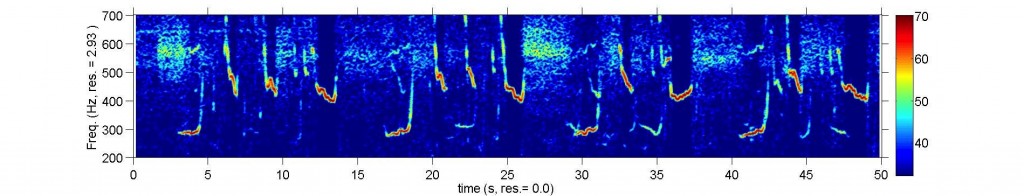

A sample sequence of a Humpback whale theme composed of moans, oohs and cries repeated 4 times over a 50 second period off the north west coast of Australia near Darwin during late August 2012. The colour code on the right side of the sonogram represents the intensity (decibels) at which the singer was singing.

“Fly-bridge – this is the wheelhouse, hey we have “carpenter-fish” – sperm whales, the bearing is to the south, see if you can see the blows, the signals are strong, the animals must be close!”

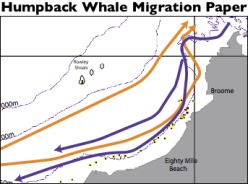

From the flying bridge of Whale Song, the cetacean observation team are looking for marine mammals in the waters just to the west of Scott Reef, a coral atoll jewel formed by twin seamounts off northwest Australia. Scanning the turquoise waters inside the lagoon and the darker, deep blue seas out to the west we are using polarising glasses and binoculars, with our cameras at the ready for any animals encountered. To date several humpback whales had been seen breaching in the lagoon and indeed sonograms of humpback whale songs appear on the computer screens linked to the sound gear. Brydes’ whale “purrs” have been recorded as well as the distinctive, low frequency booms of blue whales on the sophisticated sound receiving equipment placed on board by the Australian Defence Department. Passive acoustic monitoring now joins the tool-box of the usually visually-oriented research team, and makes it easy to detect any whale or dolphin that makes even a squeak.

The sound gear on board Whale Song is designed for locating underwater sounds, the sounds of friendly and enemy warfare. Using sonobuoys, self-deployed floating hydrophones that transmit the data via VHF radio signals, information can be collected about areas before deployment of military vessels or equipment. This basic but successful science has been employed by the Defence forces of many countries for many decades. The new twist for the CWR research team is the collection and analysis of the wide variety of whale/dolphin sounds, a source of distraction for submariners listening for the whir of a propeller, in determination of distribution, abundance and even behaviour patterns of cetaceans using the deep waters of Australia’s outer margins. In fact, some species of beaked whales are so rare and hard to detect visually that they can only reliably be located using acoustics.

As soon as the fly-bridge observation team has the word that there are whales to the south, Captain Curt brings the vessel around and we travel directly towards the bearing of the hammering sounds that the submariners in the 70’s named “carpenter fish”. Within only five minutes more excited news comes over the UHF radio used between the wheelhouse and the top deck fly-bridge. “Hey, there they are, see the blows four ahead and a fifth out to the west another half a mile, ok we are on the way!”

The whole crew is delighted with the unique angled blows of the sperm whales. They are slowly cruising northwards alongside this stunning seamount Scott Reef, warming up and recharging their lungs in preparation for another hunting dive. The body size of the whales in this group and their spacing indicates that they are likely to be a bachelor pod. They are approximately 12 metres in length and travel in parallel with each other, but at spacings of around 200m – almost like a chain of beaters working the bush to flush out game. Once they dive we hear rhythmic click trains from each whale punctuated every now and again by loud bangs. We can imagine the sonar hunting/searching technique along the seamounts’ flanks followed by sharp sonar blasts to stun the squid when they are successful in locating one.

Passive acoustic tracking has opened a new window of understanding for us into the world below, unveiling mysteries of an ocean full of intriguing noises. Combining visual interpretations with acoustic profiles of each of the cetacean species we encounter is a new and powerful system we can use to help understand the specific parts of our ocean that are the most important. Scott Reef numbers highly amongst this select group.

No comments yet.